THE DIRECTOR’S CUT

At age 18, most works of entertainment and elements of popular culture are well past their expiration date.

Time’s passing causes even original stories to seem clichéd. Special effects, at best, look old-fashioned or, at worst, are seen as campy.

It was with a little trepidation that I placed my shiny new copy of Blade Runner – The Director’s Cut into my DVD player.

Would it still seem as cool as it did the first time I saw it — in the sleep-deprived and thoroughly caffeinated state that college students seem to be able to maintain? Would Ridley Scott‘s cut add to what was already a great film?

If anything, Blade Runner has improved with age, gaining a realism that seemed otherworldly in the year of its release (1982), and director Scott’s revised version is true to the heart of the movie, avoiding the few false notes that existed in the theatrical release.

The year is 2019, and the setting is the perpetually darkened Los Angeles of the future. Science has led to the development of cyborgs, plus one better. The most advanced of these biomechanical beings, called replicants, are physically gifted and dangerously equal to their creators, intellectually-speaking. Used for space exploration and other hazardous tasks, the Nexus-6 generation of replicants was banned on the Earth’s surface after a work team rebelled, killing the humans they were supposed to serve. However, it isn’t enough to simply ban replicants. They can “pass” as people. A special police division, called the “Blade Runner Unit,” has been established to hunt down and “retire” (a euphemism for “kill”) any replicant identified as such.

The story centers around Deckard (Harrison Ford), a blade runner bullied into pursuing an especially dangerous, six-member team of replicants. After three years of life and experience, they have gained human emotions and an awareness that their life spans have been intentionally limited to four years. They want to get to their creator, the head of the Tyrell Corporation, and force him to extend their life spans — at any cost. Deckard’s search for clues to their whereabouts leads him to Tyrell and his latest “experiment”: Rachael (Sean Young), a replicant that doesn’t know she is not fully human thanks to an artificial “past” placed in her memory. In denial, once she finds out the truth, she seeks out Deckard to find what answers she can. His growing relationship with her serves as a striking contrast to his increasingly brutal and violent encounters with members of the team he has been ordered to execute.

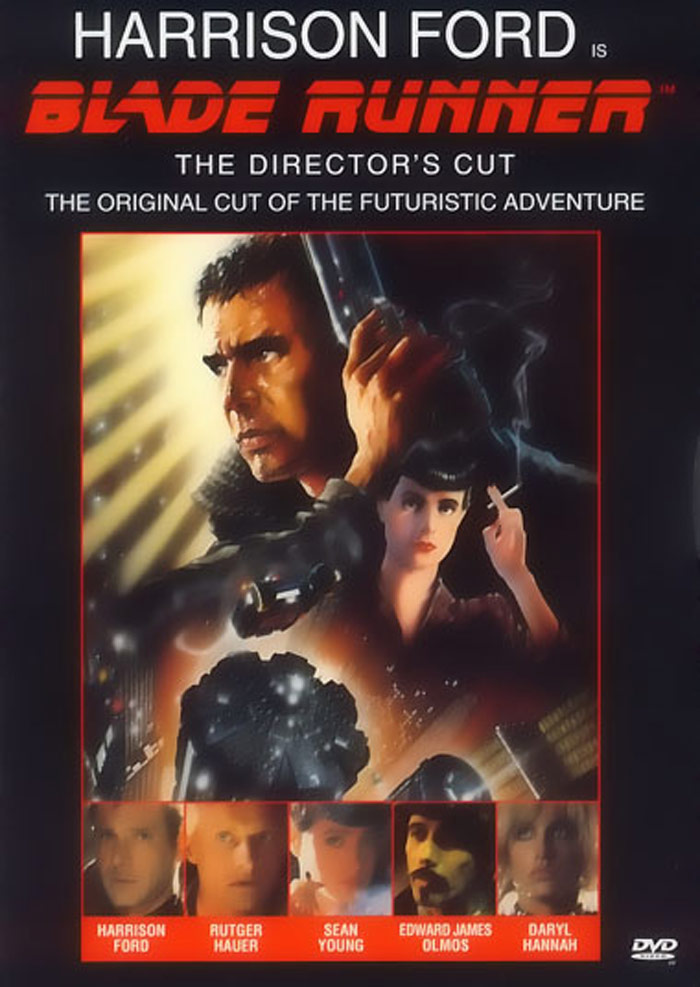

The unusually small cast of characters features standout performances by Ford, of course; Young; Edward James Olmos as Gaff, an origami-loving blade runner who speaks with an unusual dialect (not as lighthearted as that may sound); Rutger Hauer as Roy Batty, the ruthless, lethal leader of the replicants; and Daryl Hannah as the dangerous, yet childlike, replicant Pris. The screenplay, adapted by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples from Philip K. Dick‘s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, is involving — raising questions about what makes one human and how willingly we accept what we have been told is true.

But, when all is said and done, Blade Runner is truly a triumph for Ridley Scott as a director. It is a well-documented fact that, when the film was originally released, alterations, for whatever reason, were made. Alterations that Scott, as a director, did not necessarily support. With the advent of home video, it was generally acknowledged the film’s status as a “cult hit” meant there was an audience for a director’s cut of the version Ridley Scott intended audiences to experience. Released on DVD in 1999, this edition of Blade Runner is a visual treat for new audiences and offers a fresh look at the story for those who have viewed it before.

Storyline-wise, the Director’s Cut features several changes, including the omission of Deckard’s voice-over narrative. This choice emphasizes Deckard’s status as a “lone gunman,” especially at the plot’s start. Subtle scenes, further exploring his relationship with Rachael, were also added and provide a more natural bridge from where he is emotionally at the beginning film to where he is at its conclusion. An infamous dream sequence was added back in, and the “uplifting” theatrical ending was replaced with an ending more in step with the rest of the work.

With Blade Runner, Ridley Scott and his team created a bleak future reality, complete with advertisements for popular consumer goods such as Coca-Cola, Atari and Cuisenart, realistic streetscapes bustling with people of the age, and a startling visual style that, arguably, has influenced the majority of today’s sci-fi works, from anime to The Matrix.

Los Angeles, as depicted by Scott, is the grandest, dystopian metropolis of them all — complete with overcrowded streets, smog so thick that the sky is black and ever-present rain. Flying cars ensure sky traffic is just as congested as ground traffic. The lights of tall skyscrapers, the palaces of the city, serve as bright beacons. The special effects, probably the best there were in 1982, still look realistic and only add to the overall atmosphere of repressed gloom.

The intervening years between Blade Runner’s initial release and present day only serve to make the future it portrays seem more possible. Much of the technology presented is no longer just confined to the pages of sci-fi novels or the images on movie screens. However, generally speaking, human hopes and fears remain the same. Will we ever know if “androids dream of electric sheep?” Do we even want to find out? What kind of future do you want to have? Placing the questions out there, in a thought-provoking way, for us to answer for ourselves: that is the genius of Blade Runner as a work. Thank you, Mr. Scott.

More Info:

BLADE RUNNER – THE DIRECTOR’S CUT, directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, Sean Young, Rutger Hauer, Edward James Olmos and Daryl Hannah. DVD features Standard and Widescreen/letterbox versions. Rated R. 117 mins.

BLADE RUNNER is a Trademark owned by The Blade Runner Partnership. Program content © 1991 The Blade Runner Partnership. Artwork & Photography © 1982 The Ladd Company. Package Design & Summary © Warner Home Video. A Ladd Company release in association with Sir Run Run Shaw via Warner Bros. a Time Warner Entertainment Company.